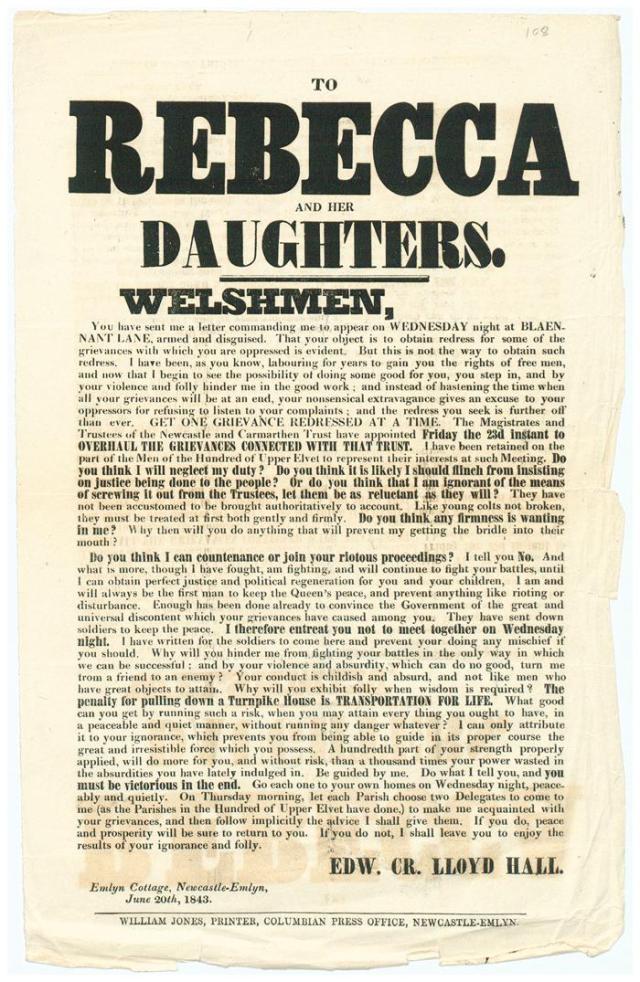

FROM: ‘A Friend of Peace and Good Order.’

TO: Edward Crompton Lloyd Hall, High Sheriff of Cardiganshire

Dated 25th Aug 1843

“…fish can go no further than Felingigfran to spawn. It has also come to my attention that the vicar of Eglwyswrw, the Reverend D. Protheroe has been feeding his sheep in the churchyard where grass grows from the putrefaction of human bodies. These sheep have been sold at Cardigan thereby proving the said Reverend D. Protheroe a cannibal…”

Rebecca: “What is this my children? There is something in my way. I cannot go on….”

Rioters: “What is it, mother Rebecca? Nothing should stand in your way,”

Rebecca: “I do not know my children. I am old and cannot see well.”

Rioters: “Shall we come and move it out of your way mother Rebecca?”

Rebecca: “Wait! It feels like a big gate put across the road to stop your old mother.”

Rioters: “We will break it down, mother. Nothing stands in your way.”

Rebecca: “Perhaps it will open…Oh my dear children, it is locked and bolted. What can be done?”

Rioters: “It must be taken down, mother. You and your children must be able to pass.”

Rebecca: “Off with it then, my children.”

*

Whatever their discipline artists get to an age where they obsess over making the big statement. Or, a la Bob Dylan, they find the principal well is dry and so make metal sculpture. Go figure, so to speak. It doesn’t matter how successful they are because the delusion is like rain and sciatica. We all get wet. We all get old. The big canvas or the turbine hall, the four movements of embedded jazz that trace the story of the cosmos in 6/8, 5/4 and why for, the translation of Dante from English into Urdu and then back again. Et al.

Write anonymous haikus; with a smile press them into a stranger’s hand; get sloshed. Repeat. Isn’t something like that worthy enough? Isn’t it worthy of you? No. You’ve got big statements to make. You’re getting older. Tick-tock tick-tock.

These photographs are from a selection taken over the past five years. Stand at my front door and this place is a weak throw of a large stone away. I thought there was a big statement here.

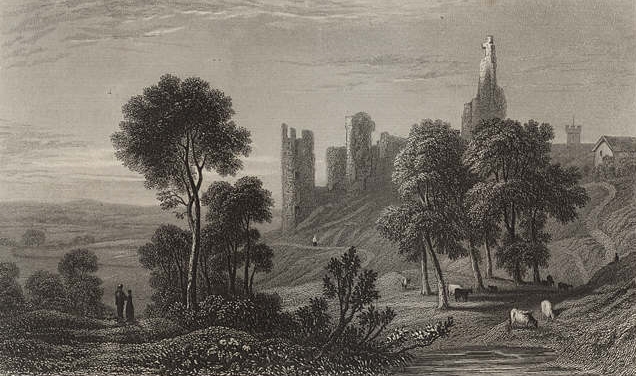

The graveyard was small but full. The graveyard is small but full. There were approximately seventy graves. There are approximately seventy graves but at least two hundred bodies and only eight or nine surnames. Typhoid, all pervading, can simultaneously fill a space and void a community. Apart from the odd exception the graveyard is populated by children and teenagers who died in the mid third of the 19th century. The paper trail is practically non-existent. I can only surmise that parents aren’t buried there because the graveyard was full by the time they passed away. To spend so little time together in life only to spend none at all in eternity. Typhoid graves are traditionally deep. Shakepeare’s tomb, rumoured to be seventeen feet down, is capped by a curse that is memorable but redundant. He is visited by thousands but left undisturbed. But his corpse, once buried, may have disturbed the fate of thousands. Later on that. Here, though, on this tiny patch, we have the disquieted that are visited by no-one.

Was to is and were to are. Is this place of rest gone now that it’s been reformulated, now that the cemetery itself has been unceremoniously buried? Or is it still there even if a car park, lawn and play area now cover the ground? It obviously isn’t a place of mourning. If it’s true that when we die we live on in the hearts of those that remember us then that ‘use’ is certainly over. Now it’s just a derelict repository. But what of me, the solipsist writer, artist, carbon earth-unit vicious for subject matter? What about the regard for lives lived, the character of my heart when I look at these images? Initially I saw them as a simple photo essay. Mary, Sister of Mary seemed like an elegant title, but it was merely neat. I graded the images on a free version of Photoshop, chucked the chaff, and filed them away as maybe the basis for a piece of writing or more likely a piece of work in itself, something enigmatic and frosty to upload and from which viewers could draw differing conclusions. Nothing wrong with gently – not idly! – allowing the images to mean whatever I impartially – not vaguely! – thought they might mean. A metaphor explicating the futility of fighting established fact? Mary’s gone so the mother haunts the next child with the name that signifies grief and let the my audience take it from there? This I could allow by saying to anyone who might possibly ask, well yes, that’s why one way of looking it at it; and then by saying no more. As Art that would do, wouldn’t it? I remember Peter Sellers being asked if he was Peter Sellers and he replying; not today: and he never was Peter Sellers. He was Richard Henry Sellers. Peter was his stillborn elder brother. So the practice of bestowing a dead sibling’s name on the living had a famous history. A few cursory chats with friends and acquaintances proved the practice more common than I thought. So, yes, as a bit of Art that would do to be getting on with. A bit of Art that with time and delusion would be construed as a Big Statement. But self satisfied isn’t the same as a satisfied self.

What gnawed was that these were real people that walked these same lanes; and I was demeaning their souls – whose existence I allow for completely; and maybe my own – at best a work in progress. Even though I’ve often hid within it I’ve always loathed the Dylan Thomas line that allowed him to look after the words only for the meaning to look after itself; and here I was doing it with images, juxtapositioning prettily and paying no heed to my obligation. What was that, though? Was it the same niggle I get when urban playwrights use the rural as a blank canvas, but cry foul if a country kid in a pith helmet turns up on their turf with a voice recorder and walks the urban talk for his or her artistic ends? What a nerve. Maybe that’s the point. Maybe I’m losing the essential reserves of chutzpah.

Maybe I’m just frightened.

Now I notice that I keep saying mother when she had a name: Elizabeth. Their father, John Howell, refuses to reveal himself to me at all. Whenever I’ve turned to this file of images I have to forcibly remind myself that he existed. A great part of me wants to recognise this as the story of four women and nothing else. I have no easy answer as to why that might be. But the absence has given me an idea of how to cast him in a drama.

He’s a Rebecca Rioter.

It was the numbers that did it. Me, the numerical dunce. I’d taken a close look at the numbers and cracked the ice. The second Mary was born the year her sister Mary died. The dates indicate that Elizabeth was pregnant at the funeral; and that their sister, Sarah, who was to die a few months later, probably stood at her side. That same year – 1843 – Rebecca rioters stormed the partially built Narberth workhouse. The Castlemartin yeomanry were summoned to keep them at bay and to guard the completion of the building. The history books say the locals were rioting against the toll gates. But it was far simpler than that. They were horrified by how closely their lives resembled eternal damnation.

This is as far as I went because something rather beautiful happened.

*

Ali Goolyad ready for action.

Tonya Smith leads a discussion of the Mary images.

Most people know who said that you can’t win anything with kids. I say you can’t lose. When The National Youth Theatre of Wales offered us at Narberth Youth Theatre a three day workshop I knew immediately what we should have its foundation: Mary Sister of Mary. Luckily everyone agreed; and it’s here that I recede into the background. For the most part all I did was listen. Tonya Smith led workshops that studied the behavioral differences in both teachers and pupils between the mid 19th c and now. A classroom was set up. The members moved between the stoic formality, with the onerous onus on repetition – but not alliteration! – of yesteryear’s teaching methods, to the social media sponsored selfawareness and pace of the superinformation multi-lane highway of education today. Music was used to set a mood, but Tonya’s sensitivity to the shifts in body language that this time travel required was the prime mover in creating strong drama from the most subtle of advice.

Ali talked of the parallels between Somali and Welsh culture. He recognised the causes of the Rebecca Riots, and was profound on how those roots paraphrase and mirror events in Somalia now. His writing workshop that accessed the minds of Welsh children who lived over hundred and fifty years ago was deeply informed by the travails experienced by Somalian children today and produced stunning results. But this was because our members responded beautifully to the task. All wrote short stories from myriad points of view which they then performed. I was struck by the ease with which the male members’ writing inhabited and gave voice to the female experience; and how the female voices brought Mary and her generation into the room in 3-D. It was a charged and emotive experience for us all. The forty minute video of these monologues is being edited and will be posted on the NYT website in the near future.

This from my notebook as I observed the sessions: Ordinary people caught up in extraordinary events is a staple… Ordinary people instigating extraordinary events ends in revolution. Mary, Sister of Mary concerns both… Physical conditions, the social fabric, the conflict of ideas… The personal drama close up, crowded in by historical events. Absent father radicalised, given purpose by the uprising fatally ignores the lives he wants to improve.

We paid a visit to the sublime Narberth Museum where there is a section devoted to the Rebecca Riots and it’s causes. This inspired part of the group to improvise a scene in a pub where the idea behind Rebecca is first raised by the disaffected. As they performed this and listened to Tonya’s notes the decision was taken to create a piece for public performance called Mary, Sister of Mary.

BRIEF NOTES ON THE BACKGROUND

John Jones

This painting by is by Thomas Brigstocke. Brigstocke was an important painter so it follows that Jones was an important man; and it can be deduced from the painting that he was also a very busy man. It isn’t the ink well or the legal papers that indicate an active life. It’s his neck. Mentally undress it and judge the distance between the shoulders and chin. Rather long, isn’t it? He could be a member of the Ndebele tribe. His trunk is also impossibly elongated. Are we looking up at him or straight on? We think we are looking from a low position but we’re not looking up his nostrils, are we? The reason for all of this is that Brigstocke would have used lenses to project an image of Jones onto the canvas, done for the sake of accuracy and speed. Jones was only there to have his face painted and only for the amount of time needed to get the correct proportions. Lenses have a limited field of view so three projections would have to be performed for this painting. The distortion is similar to the photojoiners we used to make from Polaroids in school. Collage three photos of the legs, the midriff and the chest to head and you get a similar effect to the painting of Jones. I think it would make a great scene; an impatient Jones dictating letters while having his portrait speedily painted followed by a scene illustrating the depradations resulting from his policies.

John Jones “of Ystrad” was MP for Carmarthen from 1821 to 1832. He was born in King Street, Carmarthen, the son of a solicitor. He was educated at Eton and Christ Church, Oxford before qualifying as a barrister at Lincoln’s Inn. In 1831, he was injured in rioting at Carmarthen during the general election. The voting was called off, and the election for the constituency had to be re-run in August, when Jones retained the seat. His efforts to have the salt tax abolished earned him the nickname “Jones yr Halen” (“Jones the Salt”). He was described as ‘a Tory in politics but in private life a Liberal.’ A pragmatist, then, with – to add a further detail that’s hidden in the portrait – a brass neck.

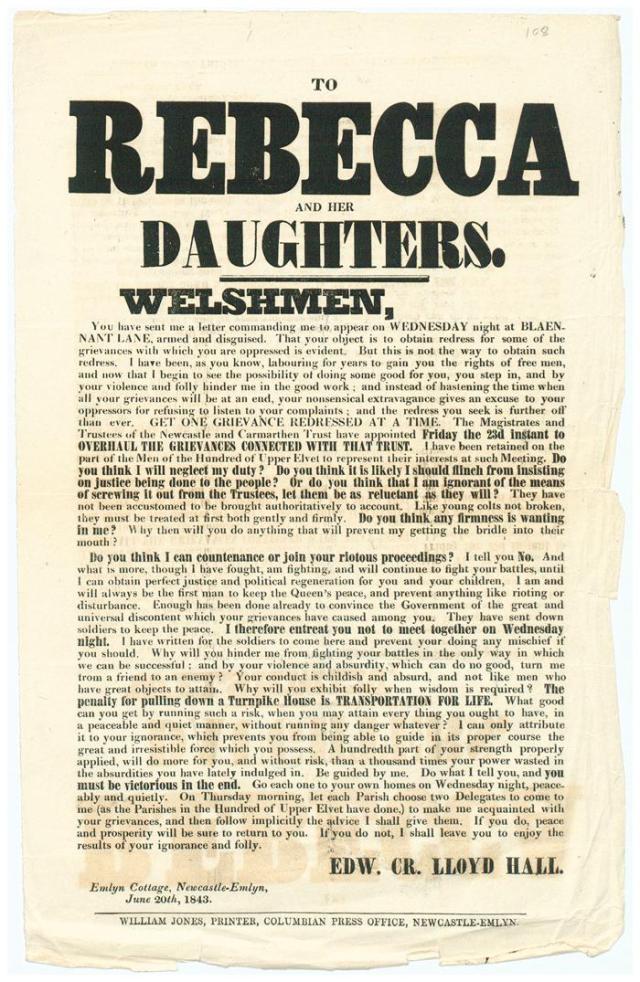

The decade preceding the Rebecca Riots was a time when any dissatisfied citizen, under the cloak of anonymity – see ‘A Friend of Peace and Good Order’ at the beginning of this piece – could find a willing printer of verbal weaponry, be it truthes or a lies, that would damage the cause of any man important enough to be the object of a personal grievance. These political or condemnatory leaflets were the modern quivalent of nameless political blogs of the ‘community pressure’ type. John Jones was often a target. “One of the Dear Little Boys” (as he described himself) alleged: “John Jones has imprisoned me and got me tried as a Rioter at the last Assizes, for doing nothing more than crying out REFORM! He has thus shown how he would use you if it was in his power. He was very glad of my services at one time, but as soon as I began to think for myself, he sent me to Prison and would have transported me if he could. I am a hard working man, but I think a little Reform would do us all good. John Jones told us last Election that he was something of a Reformer too, but I said then that we could not trust him, and now I find that I was right, for I am told that all the time he was in London he was in company with those wicked wretches called boroughmongers” (being someone who buys or sells parliamentary seats.)

The Pembrokeshire election of 1831 was bitterly contested. Remember this is before the Reform Act so the underlying story was one of family, not party, rivalry for power. Voters, only men of course and only of certain means, had to travel from all over Pembrokeshire to vote in Haverfordwest. Sir John Owen of Orielton, the incumbent MP was a Tory. He was up against reformers – Whigs – who were a tad miffed by the fact that he’d been elected unopposed four times. They set up an opponent for him, Robert Fulke Greville, a man the Irish might call a desperate chancer. Owen’s agents hung around the polling booths, ready to question every Greville supporter’s right or suitability to vote. A Pembrokeshire farmer would be surrounded and asked; are you the Pope of Rome?; Are you a peer of the realm?; Do you hold office under the crown?; Are you a lunatic?; Are you the Prime Minister? The answers to be given in writing. It sounds like Pinter. When Greville protested he was told his own agents had started this practice in Castlemartin, forty miles away. Who had time to check if this was true? Men only had horses and poor roads. If a farmer came up with unsatisfactory answers – which was likely given the nature of the questions and their browbeating delivery – then his eligibility was put to an assessor or to the High Sheriff who was, of course, a close friend of Owen. When the polls closed 300 men hadn’t voted because of these tactics. Owen won, just. Both men were bankrupted. Greville bought a pint for every man who voted for him. He had a tab in every pub in Pembrokeshire. That would bankrupt most men when you consider the fact that any house that set up a trestle and barrel was considered a pub.

When John Jones went to Haverfordwest to support Sir John he insulted Greville. A duel was arranged between the two at Tavernspite on 22nd October 1831. Jones ‘received’ as they say Greville’s shot, but he refused to apologise and fired his pistol into the air. Honour was satisfied without the interference of the law. The above painting is now in the jury room of The Guildhall in Carmarthen.

Soon the country was brought to the brink of revolution and it was the realisation of this danger that ultimately ensured the passage of the Reform Bill in 1832. In another leaflet, signed by “A Burgess”, Jones is criticised for his political record and his manners: “Everyone knows that he has talked us over pretty well for some years, but I have been often wondering why he can’t make a speech in Parliament. Is he thought of no more there than I of him, and as you all thought of him at our Slave Meeting the other day, where (in spite of the wishes of every lover of humanity) he insultingly sneered at the proceedings, although Chairman at the same time? Now the Boroughmongers and the Slave holders, with John Jones in the middle of them, were joined together to oppose Ministers in the great work of Reform — fine company indeed for our Member, after being returned three times free of expence . . . Witness how very friendly he is during, or a little before, Elections; I almost supposed him to be the pattern of humility, but as soon as that business is over, goodbye friendship, goodbye (I was going to say manners) but stop, I will give you a sample of manners. Some of us were giving vent to our feelings in a real way last evening in Spilman Street, when who came out of the Ivy Bush, but the good John Jones himself — who blackguarded us — offered to fight any of us — and at last told us to **** ourselves — there’s manners for you…”

And then there was The Poor Law of 1834. It was meant to ensure that the poor were housed in workhouses, clothed and fed. Children who entered the workhouse would receive some schooling. In return for this care, all workhouse paupers would have to work for several hours each day. Some people welcomed it because they believed it would reduce the cost of looking after the poor, take beggars off the street and encourage poor people to work hard to support themselves.

Before 1834, the cost of looking after the poor was growing more expensive every year. This cost was paid for by the middle and upper classes in each town through their local taxes. But they suspected that they were paying the poor to be lazy and avoid work. Although most people did not have to go to the workhouse, it was always threatening if a worker became unemployed, sick or old. Increasingly, workhouses contained only orphans, the old, the sick and the insane. Not surprisingly the new Poor Law was very unpopular. It seemed to punish people who were destitute through no fault of their own.

However, not all Victorians shared this point of view. Some people, such as the labour reformer Richard Oastler, spoke out against the new Poor Law, calling the workhouses ‘Prisons for the Poor’. The social reformer Jeremy Bentham, though, argued that people did what was pleasant and would not do what was unpleasant – so that if people were not to claim relief, it had to be unpleasant. Relief was to be stigmatised, “an object of wholesome horror”. Bentham also believed, ” it is the greatest happiness of the greatest number that is the measure of right and wrong.” With a certain irony Rebecca agreed, considering how support for her could be found at all levels of society.

A play then. Best get on with it; and you’ll notice that I’ve avoided the phrase, ‘contemporary resonance.’ It’s just another way of saying plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose. But the temptation to invite IDS to the opening night may well be overwhelming even if it would only be symbolic.

*

Shakespeare. Some years ago Pembrokeshire was invaded by LNG engineers, moles laying the pipeline from Milford Haven to Tirley in Gloucestershire. I was in The Eagle in Narberth with a friend of mine and we were talking about typhoid, as you do. I happened to mention that Shakespeare’s grave was seventeen feet deep and that the funeral was hastily arranged which indicated typhoid as a cause of death. One of these LNG engineers overheard this and asked whether the church was close to the river. I confirmed that it was. He nodded and commented that they buried him in the water table and that he could well have infected half of Warwickshire. Then he finished his pint and left.